Liquid or dry fertilizer products and their placement: What matters and why

Liquid or dry fertilizer products and their placement: What matters and why

This newsletter starts by addressing the age-old question about different fertilizer forms and sources. We also discuss the various placement options. Many claim that a liquid fertilizer is more efficient and more available for plant use than a dry source. For example, liquid fertilizers are assumed to be immediately available to the plant while dry fertilizers must dissolve over several days/weeks/months before they can be taken up by the plant. There are also claims that it only takes a fraction of a liquid source to equal nutrient provision by a dry source. We will discuss these two points in more detail and then expand on some of the caveats that help these claims continue to circulate.

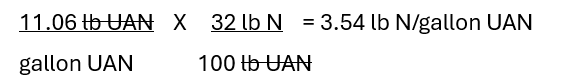

First, a pound of a nutrient is a pound of a nutrient, regardless of the source. The nutrient concentration is simply the nutrient weight per unit source weight. Using nitrogen (N) for this example, there are 34 lb N/100 lb ammonium nitrate, 46 lb N/100 lb urea, and 32 lb N/100 lb 32% UAN (urea ammonium nitrate) solution. The fact that 32% UAN solution is a liquid doesn’t change things, other than how the calculation is made. There is about 3.5 lb N/gallon 32% UAN solution. To make this calculation one needs to know the N concentration (32%) and the product density (total weight per gallon – 11.06 lb). The math follows:

The same type of calculation can be completed for any liquid source if the product density and nutrient concentration(s) are known.

The second part of the liquid versus dry discussion comes down to the difference in nutrient availability. Liquid fertilizers are often promoted as being more available to plants since the nutrients are already dissolved in the liquid source, unlike the dry solid form that must dissolve before being available for plant uptake. Dry forms do have to dissolve in the soil solution prior to being plant available. However, the time that is needed for urea and most other common fertilizers (i.e. ammonium sulfate, diammonium phosphate (DAP), monoammonium phosphate (MAP), muriate of potash, etc.) to dissolve is very short in the presence of soil water. This process usually takes minutes to hours, not days to weeks depending on soil moisture content. The amount of water needed for dry fertilizer dissolution is minimal. Regardless of the nutrient form there must be soil moisture sufficient for nutrient movement to the plant root. If sufficient water is available for nutrient movement to the plant root by mass flow or diffusion, there will be enough soil water to dissolve dry fertilizer particles. The difference in nutrient movement due to the initial fertilizer form (liquid or solid) is minimal and both forms are equally available and effective in providing crop nutrition.

One caveat to this discussion is related to some of the less common forms of fertilizers primarily used in organic crop production. These products are much slower to breakdown than many other “conventional” fertilizers. Rock phosphate contains around 25-40% phosphate (P2O5) but only a fraction becomes available in a growing season. Rock phosphates are acidulated during processing to make MAP/DAP fertilizers, which greatly increases phosphate solubility and plant availability compared to the original rock phosphate. Further, the availability of phosphorus (P) from rock phosphate is increased with grinding to a finer particle size and application to acid soils but is still far less soluble than MAP/DAP. Another example is the potassium (K) fertilizer salts. Many K fertilizers are water-soluble, crystalline salts in nature. Muriate of potash (KCl) and potassium sulfate are good examples of highly soluble K fertilizers. Conversely, a slowly soluble K fertilizer would be greensand. Like rock phosphate, greensand is not highly soluble or readily plant available. These are very different from the dry fertilizer products commonly used in commercial agriculture.

A final consideration in this discussion is fertilizer placement. Fertilizer form and placement are strongly linked. Generally, fertilizer placement in a band, both on or below the soil surface, is easier with a liquid product than a dry product. The most common band applications occur at planting, either in the row (in-furrow) or 2 inches over from and 2 inches below the seed furrow depth (2x2). The placement of either dry or liquid fertilizers will provide equivalent amounts of available nutrient to the plant, assuming all other factors are the same. However, there are some different fertilizer properties to consider when banding nutrients, dry or liquid. In-furrow placement raises the potential for seed damage/delayed seedling emergence/reduced stand. Products like KCl (dry product) have a high salt index that can have detrimental effects on seed germination. A similar response due to high salt index can be observed with potassium thiosulfate (liquid product). Band applications of both products are based on pounds of K2O per acre, regardless of the form. Liquid sources are typically easier to handle in many situations and often require fewer stops at planting. Saddle tanks for a liquid source on the pulling tractor can often hold more fertilizer than dry fertilizer boxes on the planter.

Most micronutrients are available in both dry and liquid forms, but micronutrient source choices are more dependent on effective placement because of the small amount of nutrients needed to meet crop needs. Some dry micronutrient materials are difficult to use and spread via bulk blends. Dry micronutrients can be found co-granulated with either MAP or KCl, which improves their distribution spread as a bulk blend. More often water-soluble micronutrient production system. A liquid source may be favorable to a dry source when applying nutrients at planting or sidedressing, but plant availability will be similar regardless the form. When it comes down to using a liquid or dry fertilizer source, make sure to consider all the factors behind the decision: price and management options.

As the American poet Gertrude Stein said – a rose is a rose is a rose. The same generally holds true for fertilizer – fertilizer is fertilizer is fertilizer. When deciding which nutrient source to use, it simply comes down to two things. The first consideration is cost of different sources. Unless there is an agronomic performance reason or management advantage for one source to be a better choice than another, price matters. The second consideration is what works best in the individual operation, especially equipment considerations.

| Citation: Ritchey, E., Grove, J., 2025. Liquid or Dry Fertilizer Products and Their Placement: What Matters and Why. Kentucky Field Crops News, Vol 1, Issue 10. University of Kentucky, October 10, 2025. |

|

|